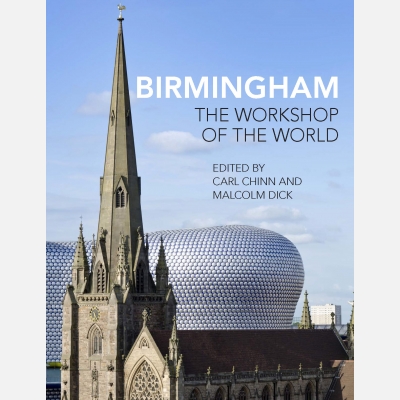

Birmingham: The Workshop of the World

Limited Edition in protective sleeve

Was £35.00,

Now £30.00

- A celebration of the city’s history and achievements, revealing the wonderfully rich diversity of Birmingham’s people.

- Illuminating little-known aspects of the city’s history as well as rethinking traditional events and activities.

- Presenting up-to-date historical and archaeological research to a general readership: locally, nationally and internationally.

- Written by experienced and distinguished scholars.

- Lavishly illustrated with historical images, photographs and maps.

Chapter contents:

Introduction: Birmingham, from past to present – Carl Chinn and Malcolm Dick

Birmingham has been an important urban centre, not only in British history, but also internationally. Its history can be explored in many different ways: via its scientific accomplishment, industrial innovation, political leadership and cultural diversity, for example. The authors explore the changing contours of Birmingham’s experience, by looking at how images of the town and city have changed from the first descriptions of visitors to the writings of historians, journalists and others, whether they lived in Birmingham or arrived from outside.

Outside observers described Birmingham as ‘the ‘city of a thousand trades’ and ‘the best governed city in the world’, but Birmingham has also acquired a reputation for intellectual achievement, religious and racial toleration and an outward-looking culture. Birmingham has many histories and this book attempts to explore them from earliest times, before the town existed, during its emergence as a market town, throughout its industrial growth and evolution and its emergence as a global city.

Before Birmingham: the Prehistoric and Roman periods – Mike Hodder

Our knowledge of Birmingham before the Anglo-Saxon period is derived from archaeological remains - objects found by chance, excavated structures and objects and surviving features- supplemented by pollen, seeds, beetles, soils and sediments which provide a vivid picture of the landscape and people’s exploitation and management of their environment. The story begins with the stone handaxes of Palaeolithic people living in warm periods between glaciations, followed by the flint tools of their Mesolithic successors who hunted in birch and pine woods ten thousand years ago.

The first farmers in the area, in the Neolithic period, still lived in a wooded landscape and have left relatively few remains- the first significant clearance of woodland took place three thousand years ago at the time of the enigmatic Bronze Age burnt mounds, and resulted in soil erosion. In the few centuries before the Roman conquest, Iron Age farmers lived in circular houses in ditched farmyards, and there were areas of heathland used for rough grazing. The invading Roman army built a fort and roads. Some existing farms continued in use and others developed along the roads. Paddocks and enclosures were probably for livestock management. Pottery kilns produced vessels used at the farms and other settlements.

Medieval Birmingham – Steven Bassett and Richard Holt

Birmingham’s pre-burghal history, although vestigial, is nonetheless recoverable in bare outline. In the late Roman period the Birmingham area was crossed by important through-routes, most of which survived into the modern era, and it supported mixed farming. Much woodland regenerated in the post-Roman period but agriculture continued, if on an initially reduced scale. An extensive territory formed by the area’s Anglo-Saxon inhabitants eventually fragmented by stages into the many manors recorded in Domesday Book, with its parochial organisation apparently centred on Harborne. Among these manors Birmingham was relatively small and insignificant. By the 1160s its manor-house occupied a defensible position near to a through-route’s crossing of the River Rea on the manor’s southern boundary. A triangular market-place with adjacent burgages was laid out along the road. In time a chapel, St Martin’s, was built in the market-place, supplementing and at length replacing Birmingham’s original church, which stood upslope to the north-west.

Birmingham’s importance as a commercial centre began formally with the establishment of a market in 1166. Probably simultaneously, Birmingham’s owners encouraged its growth as a community of craftsmen and traders by splitting the manor into the borough (with its own court and administration for the new urban population) and the foreign (with the original court for the agricultural population). Birmingham’s transformation into a small town was rapid, so that within a century of the market charter it had acquired a population of perhaps 1500, and an extensive market area in northern Warwickshire and Worcestershire and south Staffordshire. Something of the town’s social structure is recoverable from the recently discovered borough rentals of 1296 and 1344-5. By the fifteenth century Birmingham had become a cattle-marketing centre of regional importance; in addition, by 1500 it was prominent for its large metal-working industry, particularly the production of edged tools and weapons. After 1500, the town began another period of rapid growth as it developed its role as the marketing centre for the rural metal-working industry of its large hinterland.

Birmingham in the Tudor and Stuart period – Richard Cust and Ann Hughes

This chapter will explore the rise of Birmingham from a large village in the early sixteenth to, perhaps, the biggest town in the midlands, with a population of 7-8,000, in the late seventeenth century. It will investigate the role of metal working industries in this growth. Already established in the region at the start of the period, they developed rapidly with technological developments such as the blast furnace and the slitting mill leading to a substantial rise in local employment which fuelled the population increase. It will also explore issues of local governance and politics in a town which from 1530 onwards had no resident lord of the manor, but which was still subject to the influence of the Holtes of Aston. This situation created a relatively fluid and open society in which the middling sorts could pursue their interests largely free from the ties of deference and paternalism. Also considered, religion in these developments, as Birmingham became a centre for puritanism and, after 1660, dissent. Alongside analysis of these long-term developments there will be an investigation of key episodes, such as the English Civil War when part of the town was burnt down by Prince Rupert because of its support for parliament.

Birmingham: city of a thousand trades c. 1700 to 1945 – Malcolm Dick

Why did Birmingham emerge as a rapidly growing industrial centre in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries? What was distinctive about the local industrial experience compared to other industrial towns? To what extent and why did the economy prove to be adaptable to change in the early twentieth century? This chapter explores and explain the shifts in local economic life from the early toy trades, lock making, gun making and japan ware, to the development of the printing industry (Baskerville), metal manufacturing and heavy engineering (Boulton and Watt), the pen trades (Mitchells, Gillotts and Mason), screw manufacturing (Chamberlain and Nettlefolds) and jewellery and silverware. Birmingham also developed important institutions such as the Assay Office, the Proof House and banks to support industrial enterprise. Cultural influences are explored critically, including the significance of nonconformity, the scientific Enlightenment (Lunar Society), the transfer of skills and the importance of migration. Birmingham’s achievements were revealed in international exhibitions, the creation of industrial districts, such as the Jewellery Quarter and industrial buildings, some of which still survive, but foreign competition was an increasingly important influence which began to threaten Birmingham trades from the mid-nineteenth century. Twentieth-century experiences include the impact of war and the growth of consumer industries such as food processing (Birds, Cadburys, HP Sauce, Typhoo), from nineteenth-century roots, bicycle and car manufacturing (Raleigh, Austin and others), BSA and electrical engineering (Lucas). The alleged significance of nonconformity, the importance of entrepreneurs, artisans and women workers, the role of transport (roads, canals and railways) and the contributions of technology, banking, retail and the service industries to the evolution of a complex economy are underlying themes.

Birmingham’s political history – Roger Ward

Leland’s ‘goode market town’ of Tudor times by the eighteenth century was becoming an industrial powerhouse. But in contrast with the institutional sophistication of incorporated towns in the region: Coventry, Warwick, Lichfield, its governance remained primitive, a hotchpotch of parish and manorial institutions. A much-needed Act of 1769 established the Streets Commission which until its abolition in 1851 carried the main responsibility for local government. An elite unelected body it navigated Birmingham through the Canal and Railway Ages, leaving a legacy of impressive buildings. In the post-Napoleonic period the cry for reform went up from Britain’s major towns. In Birmingham George Edmonds led the Hampden Society until his role was superseded by Thomas Attwood, ‘King Tom’.

The Birmingham Political Union was the most important of the Political Unions which pressured the government into the Parliamentary Reform of 1832. The BPU established Birmingham’s radical tradition, carried on most effectively by John Bright and then in the 1880s by Joseph Chamberlain. The Birmingham ‘caucus’ was a by-word for efficient political organisation. An extraordinary hiatus occurred in 1886 when Chamberlain quarrelled with Gladstone, rejecting Irish Home Rule. In the years that followed he wrenched Birmingham away from Radicalism to become Unionist, a situation which lasted under his sons, Austen and especially Neville, whose demise in 1940 marked the end of Birmingham Unionism and of Birmingham’s ‘exceptionalism’ amid a welter of controversy over Appeasement. In 1945 the Birmingham Labour Party came at last into its own. Birmingham’s influence in national politics cannot be overestimated. Attwood, Bright and the Chamberlains spearheaded causes which changed the politics of the nation for better or worse.

Education in Birmingham from the eighteenth century – Ruth Watts

Birmingham has made a distinctive contribution to education. Through the small but influential Lunar Society meeting in Birmingham and the West Midlands, radical ideas of enlightened education were diffused nationally and abroad. Despite the setbacks to progressive ideas occurring in the French wars, radical ideas continued to develop in Birmingham in the nineteenth century mainly through the schools of the Hill family who won an international reputation for progressive methods of school organisation, curricula and teaching and the educational efforts for the poor of Unitarians, Quakers and others. Through such groups Birmingham led the National Education League in the 1860s which was crucial in the advent of national elementary education from 1870. Thence Birmingham, dominated by its Liberal elite, was a leader in Board school education. From the 1870s it also extended its grammar and high school provision for boys and set up private and endowed schools for girls, two of which became outstanding in the leadership they gave in female education, not least in science. Initiatives in higher education, in medicine and through Mason Science College led to the opening of the University of Birmingham in 1900 which incorporated both these and Mason’s Department of Education, itself developing from the Day Training College for women. In the twentieth century Birmingham had some prestigious provision, notably in higher and technological education and provides an interesting history of education with regard to equality of racial and gender opportunity and special needs. These histories are investigated to answer how far Birmingham has been an ‘enlightened’ city of education.

The arts of industry – Sally Hoban

This chapter explores the history of architecture, art and design in Birmingham, with a particular focus on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The history of the arts and art education in Birmingham reflected the needs of local manufacturing, private and public patronage, the city’s international links and the expansion of education. Crucial to the history of art and design were two major institutions: Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery and the Birmingham Municipal School of Art. Birmingham provided training and professional opportunities for both men and women artists and became a centre of production in the Arts and Crafts movement. Jewellery, silversmithing, metalwork, stained glass, textiles and book illustration were important examples of Birmingham’s contribution to the history of the decorative arts. Civic, commercial, religious and residential buildings provide the parameters for the examination of architecture. Focal points include St. Philips, Birmingham Town Hall; the architecture of the Civic Gospel, such as the work of John Henry Chamberlain; the Arts and Crafts Movement, including the work of William Lethaby and William Alexander Harvey at Bournville and Modernism and Brutalism, finishing with the work of John Madin. Painting is explored through the Lines family, David Cox, the early days of the RBSA, Birmingham’s support for the Pre-Raphaelites and the influence of these artists on Birmingham painters. The Birmingham Group of artists who trained and taught at the Birmingham Municipal School of Art in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were instrumental in the tempera painting revival (Kate Bunce, Joseph Southall). Twentieth-century developments include the work of Bernard Fleetwood-Walker and the Birmingham Surrealists.

Health care in the heart of England – Jonathan Reinarz

This chapter will survey the history of medicine and health in Birmingham from the eighteenth century through to the twentieth century. It will examine the industrial development of Birmingham and the way in which a medical marketplace began to emerge in the eighteenth century that was not restricted to orthodox practice alone. It will examine the careers and practice of some local physicians, surgeons and apothecaries, but also some of the itinerant and unorthodox practitioners who peddled their wares to a population which was growing progressively more affluent. It will begin to examine the influence of rapid population growth and industrialisation on the health of the population, but will also consider the ability of Birmingham’s inhabitants to pay for health care, in the form of hospitals (general and specialist), asylums and dispensaries, midwifery care, as well as medical education. While focusing on institutional medicine, it will also consider the wider field of public health, the impact of epidemics, medical interventions, such as vaccination and the work of the medical officer of health. It will conclude by considering the health of Birmingham’s working population, which did not rely entirely on doctors and institutions, but improvements in housing, local infrastructure and even education. It will conclude by considering the state of health in a post-industrial and multi-ethnic Birmingham.

Printed in Birmingham – Caroline Archer

Printing is the fourth largest industry in the UK, and Birmingham is arguably Britain’s foremost printing city. Home to John Baskerville type-founder, printer, paper-maker, ink-producer and creator of ‘Baskerville’ one of the world’s most well-known and enduring typefaces, Birmingham was at the centre of European printing during the mid-eighteenth century. However, Birmingham’s contribution to printing history does not simply lie with the memory of Baskerville, and for more than three centuries the city’s printers, typefounders, typographic educators, bookmakers, booksellers, and newspaper publishers have made Birmingham not only a national, but also an international typographic-force. Printing history inevitably concentrates on the London press, yet Birmingham, which became the largest centre of the trade outside London, had a distinctive printing industry whose printing houses, such as the Kynoch Press, contributed significantly to the technical and economic progress of the world-wide printing industry in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries; a pre-eminent School of Printing, which did much to influence the intellectual and aesthetic typographic landscape both in the UK and abroad, particularly under the influence of the designer and teacher Leonard Jay; and a forward-looking union that helped democratize the printing-trade union movement. Birmingham has a long history of publishing books, pamphlets and newspapers, which have made their own contribution to print culture.

Challenge and change: the politics of post-war Birmingham – Matt Cole

This chapter challenges critical assessments of post-war developments in Birmingham by exploring the issues, personalities and policies dominating Birmingham’s public life after the Second World War and the end of the Chamberlain dynasty. It sets key developments in the context of the past and of the fortunes of the region and the country, and points to key determining features of the city’s government. A survey of Birmingham’s Parties, elections and government includes changes in local government funding, powers and structure including the loss of local control over hospitals and schools, the development of the cabinet system and the Mayoral referendum of 2012; the transition from two-party politics to three-party politics, including reference to the 2004 election court as an illustration of the intensity of party competition; and leading personalities of the post-war era including significant council leaders and MPs with a national profile. Birmingham’s response to the challenge of economic change is assessed in a section covering the structural decline of industry, notably motor manufacture, and responses to this from local, regional and national authorities. There is analysis of the impact of national recessions on the Birmingham economy, and of continued public investment projects including redevelopment of the Bull Ring, the NEC, and Broad Street. The final subject of this chapter is Birmingham’s people and social policy, including education and housing: post-war expansion in municipal provision of housing; wider accessibility of education and controversy over structure. Race relations are examined: the political response to phases of immigration into Birmingham and their impact on political processes; and crime and policing – methods of policing, levels of crime and episodes of public disorder – are surveyed. The chapter ends with a defence of Birmingham’s continuing status as Britain’s second city, and its continuing political distinctiveness from the rest of the region and the country.

Many peoples, one Birmingham – Carl Chinn

Birmingham today is the most multi-cultural city in Britain outside London. Yet, if the different peoples of Birmingham are so obvious on the streets of the city, then many of them have been conspicuous by their absence from its histories. Older accounts of the origins and growth of Birmingham have focused on the wealthy and those who are well known for their impact politically or economically. These influential general histories are supplemented by a plethora of biographies and company histories which have focused on leading personalities in the history of Birmingham. Works in this vein are indispensable if we are to appreciate the key events and men who have played such a crucial part in the making of Birmingham, but the paucity of material relating to majority of Brummies before about 1900 is obvious and needs to be addressed. Indeed it was not until the 1980s that an outpouring of working-class life stories really began. It is essential that a chapter on the Peoples of Birmingham highlights not only 'great men' but also those who have been hidden from history for too long. This means that attention must be paid to women as well as to men; adults as well as children and teenagers; and the working class as well as the middle classes. Moreover it is vital that such a chapter engages positively with all the ethnicities of Birmingham as well as with the history of people with disabilities. Thus, it will be the aim of this chapter to bring to the fore, as much as is possible, all of the peoples of Birmingham and to highlight their collective contributions and not just those of elite individuals.

Additional features:

- Timeline of the history of Birmingham.

- Illustrated with colour and black and white illustrations, maps and photographs distributed among the text throughout the book;

- Boxed text sections, highlighting key aspects of Birmingham’s history for more prominence.

Cover: Hardback with protective sleeve

Size: 24.2x2.8x18.8

For your security, we do not store any card details on our site.